Wardriving in London 2007

Conducting regular research into WiFi networks and wireless protocols can help us gain a better understanding of the true state of affairs in this area. When possible, we try to shed some light on these issues in our articles in order to keep computer users informed. Our research focuses on WiFi hotspots and mobile devices supporting Bluetooth.

We hare already published overviews of wireless networks in the cities of Beijing and Tianjin, networks running during CeBIT 2006, and the results of our research from London, Paris and Warsaw.

One year after our first London study, we returned to the city in order to collect new data and evaluate recent developments for ourselves. We also wanted to see if, based on our data from November 2006, Paris would still hold the record as the best-connected city.

The research was conducted between April 24th – April 26th, 2007 in the London business districts of Canary Wharf and City, as well as other areas of the city. During our wireless tour, we collected data on 800 hotspots. No attempts were made to intercept or decrypt traffic on any wireless networks.

We detected the following hotspots:

- Canary Wharf: over 400 hotspots

- Other areas of London: over 400 hotspots

This article will address the changes which have taken place since our last wardriving tour of London in 2006.

Transmission speed

Transmission speed: Canary Wharf

Transmission speed: London

Our research in Canary Wharf shows that the number of networks running at 54 MB was over 82%, up more than 14% from 2006 (when it was 68%). The numbers for this London district have exceeded those for the equivalent business district in Paris, La Defense, where results showed 77% (November 2006).

We continued to see an interesting pattern in the business districts of European capitals: the transmission speed of wireless networks tend to be lower than in other districts of the same city. Last year, Canary Wharf was 4% – 5% slower than the rest of London, and La Defense was 8% slower than the rest of Paris (77% and 85%). This year, the speed of networks in London has increased, but the lag between Canary Wharf and the rest of the city remains at 5% (82% and 87%).

The second most common speed is 11 MB, which is steadily losing popularity. Last year more than 25% of the networks detected at Canary Wharf were running at this speed, and this year that number is down to just 16%. The percentages are even lower for the greater London area, having fallen from 28.6% to 12%.

The number of networks running at a speed of 22 – 48 MB did not exceed 2% anywhere in the city, but we did find devices running at 16.5 MB for the first time.

It’s safe to say that the transmission speed of wireless networks in London has increased significantly, and this city is currently the absolute leader in terms of transmission speed when compared to the other cities we have researched. The city’s average is 87% at 54 MB, which is in striking contrast to Warsaw, for instance, with a mere 14% of networks running at this speed.

Equipment manufacturers

A total of 26 different manufacturers were detected, which is slightly less than the 33 manufacturers we identified in 2006.

In the Canary Wharf district, equipment from 16 different manufacturers was found, five of which are the most common and used by 15% of the networks.

The equipment of the other 11 manufacturers is used in less than 10% of the networks.

The volume of unidentified equipment (Fake, Unknown, or User Defined) increased from 10% in 2006 to 76%.

Cisco was able to maintain its foothold at Canary Wharf, despite the amount of equipment from this manufacturer having almost halved in number. CyberTAN was squeezed out of second place by Airespace, a manufacturer that was not featured in our previous reports.

In London as a whole, as we noted above, we identified 26 manufacturers. Equipment from the top five manufacturers was used in 15% of all networks, just as in the Canary Wharf district.

The volume of unidentified equipment (Fake, Unknown, or User Defined) grew from 15% in 2006 to 76%.

The main difference between the London as a whole and the Canary Wharf district is the top five manufacturers.

Cisco was squeezed out of first place by CyberTAN, and Aruba and 2Wire have lost ground to Linksys and Airespace. Only Netgear’s share has not changed.

Traffic encryption

The most important and interesting factor when it comes to wireless networks is the correlation between secure and unsecured hotspots. Since we first started wardriving in 2005 in Beijing and Tianjin, each city we investigated set new records in this area.

Beijing’s figures showed less than 60%, which was down to 55% at CeBIT 2006. London in 2006 was recorded at 50%, and Paris seemed to have achieved the unachievable with only 29% of networks not using encryption. Warsaw did fairly well this spring – better than London – with 42%.

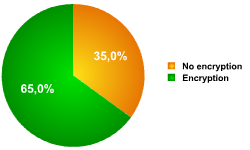

We were happy with the results we found during our visit to the British capital this year. First let’s take a look at the numbers for Canary Wharf.

Canary Wharf demonstrated excellent figures with just 35% of networks running without traffic encryption in this enclave of numerous skyscrapers, including Great Britain’s tallest building, the 238-meter Canada House. This district is also home to a number of international banks (HSBC and Citibank to name a few), insurance companies, news agencies, etc. These are the very organizations that could be targeted by hackers and fall victim to the theft of commercial information.

Only a year ago 40% of all networks in this district were unencrypted. On the one hand, this clearly shows an increase in the number of secure networks. Canary Wharf has even managed to outdo La Defense, which registered at 37% in November last year. On the other hand, the improvement was just 5%. Just as before, over one-third of all hotspots could become the targets of hacker attacks. Furthermore, this increase took place while the total number of hotspots more than doubled. In the end, the new networks aren’t that much different from the older ones, and clearly not all potential threats – which have been recognized for years now – are taken into consideration when these networks are set up.

Even worse is that once again, London’s overall traffic encryption proved to be better than that of the business district. This was also noted in Paris (29% for the city as a whole, 37% for La Defense). Last year, Canary Wharf had better numbers than London as a whole, but has slipped this year with 31% of networks being encrypted as opposed to 35% of networks in the rest of the city.

Consequently, the figure for London overall has improved by almost 20%. The British capital only needs to work a little more on its networks in order to surpass Paris, but the numbers are now so close that we can say these two cities are on an equal footing. London’s business district, however, needs to make some improvements in order to achieve the level of wireless security enjoyed at La Defense.

Types of networks

Wireless networks may be created around ESS/AP hotspots, or as Peer/AdHoc (computer-to-computer) connection.

It is known that nearly 90% of all WiFi networks worldwide use ESS/AP hotspots.

In 2006 Canary Wharf’s figures were almost identical to figures worldwide. This year the number of peer-to-peer connections fell slightly and amounted to 7%. This may indicate that WiFi devices with this kind of connection are decreasing in popularity (printers, for example), although overall these figures are within the margins of error.

The figures did not change much for London as a whole (unlike Canary Wharf) and showed a slight increase in the number of peer-to-peer connections. At just 1%, this increase is very small, but considering the total rise in the number of wireless hotspots in London, we can see that this trend is clearly indicative. Perhaps in the future London will catch up with Paris’s 13%.

Default configuration

Networks with default settings are a juicy target for hackers who specialize in wireless networks. As a rule, the SSID default means that the administrator of the hotspot has not changed the name of the router. This also indirectly shows that the account administrator is using the default password. It is very easy to find information about default passwords for different equipment makes and models on the Internet. Once a hacker knows the manufacturer (see Equipment manufacturers) a hacker can gain full control of a network. In London in 2006, default settings were found on 3.68% of the city’s networks and slightly over 3% of Canary Wharf’s WiFi hotspots.

One of the most effective means of protection against wardriving is disabling the SSID. The chart below shows a breakdown of the networks found according to these two factors.

As the graph shows, the default SSID figures for Canary Wharf halved to 1.5%. However the number of networks with disabled SSIDs has fall from a record 30% to a more modest 19.4%.

La Defense is still in the lead for this category, with 26% of its WiFi networks using disabled SSIDs.

It may seem odd but the decrease was noted for London as a whole as well, from 32% to just over 13%. The drop in networks using default configuration from 3.68% in 2006 to just 1.07% in 2007 is a positive sign and is a new record low.

Subliminal advertising

One interesting phenomenon is the tendency to use hotspots for subliminal advertising. Every client attempting to connect to a network will look at the list of accessible networks. Using web addresses as hotspot names can serve as an additional means of attracting new clients to the site. The first networks that we saw using this technique were in Warsaw, where they accounted for roughly 3% of all networks. This approach was found in London as well, and although only 1% of WiFi networks used this tactic, it can still be seen as a certain trend.

Conclusions

The points below provide a summary of our most recent wardriving:

- There has been a steady increase in the use of new wireless equipment working at 54 MB. 87% is the best figure we have seen to date.

- The gradual progress in terms of traffic encryption on wireless networks still leaves plenty of room for improvement.

- Business districts are still lagging behind when it comes to security, compared to the figures shown by the city as a whole.

- The number of hotspots has nearly doubled, especially in the Canary Wharf district. We have tried to follow the same routes as one year ago during the same amount of time. The increased popularity of wireless networks is remarkable.

- London’s key wireless network figures are now more or less the same as those in Paris.

This year we opted not to conduct a separate study of the hotspots at the InfoSecurity in London. Our observations at CeBIT 2006, InfoSecurity in London and InfoSecurity in Paris in 2006 demonstrate that all our figures were almost identical across all the exhibitions. During InfoSecurity 2007 in London we did detect a certain number of hotspots with default configuration which became the target of attacks and jokes. For example, one such hotspot boasted a proud new name on the second day of the exhibition: “Hacked by Kevin Mitnick.”