Review: Group-IB Fraud Hunting Platform

Today’s Internet is a hectic place. A lot of different web technologies and services are “glued together” and help users shop online, watch the newest movies, or stream the newest hits while jogging.

But these (paid) services are also constantly threatened by attackers – and no company, no matter how big, is completely immune. Take the recent Twitter compromise as an example: the attackers hijacked a number of influential Twitter accounts, including those belonging to Joe Biden, Jeff Bezos, Apple and others, and used them to try to pull off a Bitcoin scam. The attackers took advantage of the whole remote working situation, targeted the Twitter support team through a phone spear phishing attack, and successfully phished VPN credentials that enabled them to access the company’s internal tools.

How can companies protect their services from similar attacks, as well as identity takeovers due to successful exploitation of stolen information such as credit card numbers, user account credentials and authentication tokens?

In this review, we will take a close look at the Fraud Hunting Platform (FHP) developed by Group-IB, which helps web and mobile service owners monitor users’ usage and investigate potential misuses. Aside from detecting anomalous use of a service, Group-IB’s FHP allows service owners to detect when users are infected by malware that can perform Man-in-the-Browser attacks or alter pages, facts of remote access to a user device, and automated bots looking to access the service and siphon data (e.g., product prices in e-commerce applications).

Test methodology

We used a pre-configured test instance of the Fraud Hunting Platform that monitored two demo sites that require users to create an account and log in to browse products, order them and send the payment.

We tried standard and non-standard attack tactics and techniques that anti-fraud tools should be able to detect. Those include:

- The use of proxies to change the IP/location. VPN hopping

- The use of remote access tools (Teamviewer, RDP, VPN) by some trojans

- Access through TOR exit nodes

- The use of emulator and virtual machines

- The spoofing of User Agents

- The use of Selenium and scripted bots that try to brute-force the login form

- The manipulation of web pages (JavaScript injections)

- Mobile access tests

After going through each of these test cases or a series of them, we assessed the effectiveness of the Fraud Hunting Platform based on the following criteria:

- Did it detect the relevant event?

- What threat level has it assigned to the event? Are threat levels related to the potential risk represented by the test case?

- Are FHP detections helpful to threat/fraud analysts? Can the FHP improve the process of detecting fraud and potential misuses?

- Usability and ease of use of the FHP web interface

The Group-IB Fraud Hunting Platform

The Group-IB Fraud Hunting Platform is a digital identity protection and fraud prevention system designed to protect end users from various types of online fraud.

Fraudulent or bot activity detection is based on fingerprinting user sessions and identities (by using device and network-related information) and user behavior patterns (mouse movements and clicks, keystroke dynamics), which means that there is no need to write specific rules that detect abnormal/fraudulent behavior.

The FHP enables service owners to perform a global profiling of fraudulent activities across their resources or cross channel analytics (if the needed permissions are provided). That means that they can follow attackers as they are exploiting various services, which can be useful for investigating bigger incidents.

The FHP can detect bots and other attack patterns: malicious injections, attempts to leverage remote access tools, compromised devices, SIM card changes, and so on. It can detect threats to financial and e-commerce sites, cryptocurrency exchanges, social networks and other online services.

The FHP can deliver value to customers by blocking malicious users that request authentication tokens while trying to brute-force accounts with the targeted service. If the services owner delivers authentication tokens via SMS, such attacks can result in increased costs. Other use cases include detection of users that exploit stolen payment card data or perform fraudulent activities related to user reputation (e.g., boosting reputation as a fake seller on e-commerce sites).

The platform also enables service owners to manage their users better, prevent the locking of wrong accounts, and manage transactional limits better. According to Group-IB statistics, up to 85 percent of sessions that are subject to extra analysis, can be automatically accepted thanks to additional data and FHP verdicts. The FHP is also useful for detecting compromised systems that are accessing the service’s resources – a capability requested by the EU Payment Services Directive 2 (PSD2).

How does the Group-IB Fraud Hunting Platform work?

The main components of the FHP are the client module, the Processing Hub, the Preventive Proxy and the analytical web interface.

The service owner first needs to embed a lightweight data collection script on the client side:

- A simple JavaScript code snippet is embedded into websites to collect data related to user’s device and browser settings and user’s behavior within the application

- In cases where the service is a standalone mobile application, the FHP provides a mobile SDK that performs the collection of user action and context data

Both the mobile SDK and the code snippet have a minimal effect on the mobile phone or computer resources usage (network traffic, CPU/RAM usage) and application functionality.

The collected data is sent and analyzed by the FHP Processing Hub, which extracts relevant information (session and identities, user actions) and detects abnormal behavior that enables the fingerprinting of bots. Bots are blocked by the Preventive Proxy.

The processed data can be viewed via a handy web interface that provides a clear overview of the monitored sites. The interface allows the service owner to:

- View fraud alerts categorized by risk

- Pivot through all events by identities, devices and sessions

- See detected and blocked bots

- Investigate incidents from a higher level with a graph analysis

- Search events by various fields, and more

The FHP’s modular design enables various configurations related to blocking bots, but it also enables integration with other transactional fraud detection systems that companies use for monitoring financial transactions. At the moment, integration with systems by SAS, Bottomline (Intellinx), RSA Transaction Monitoring, and GBG are available.

Figure 1. Fraud Hunting Platform – Dashboard showing recorded events

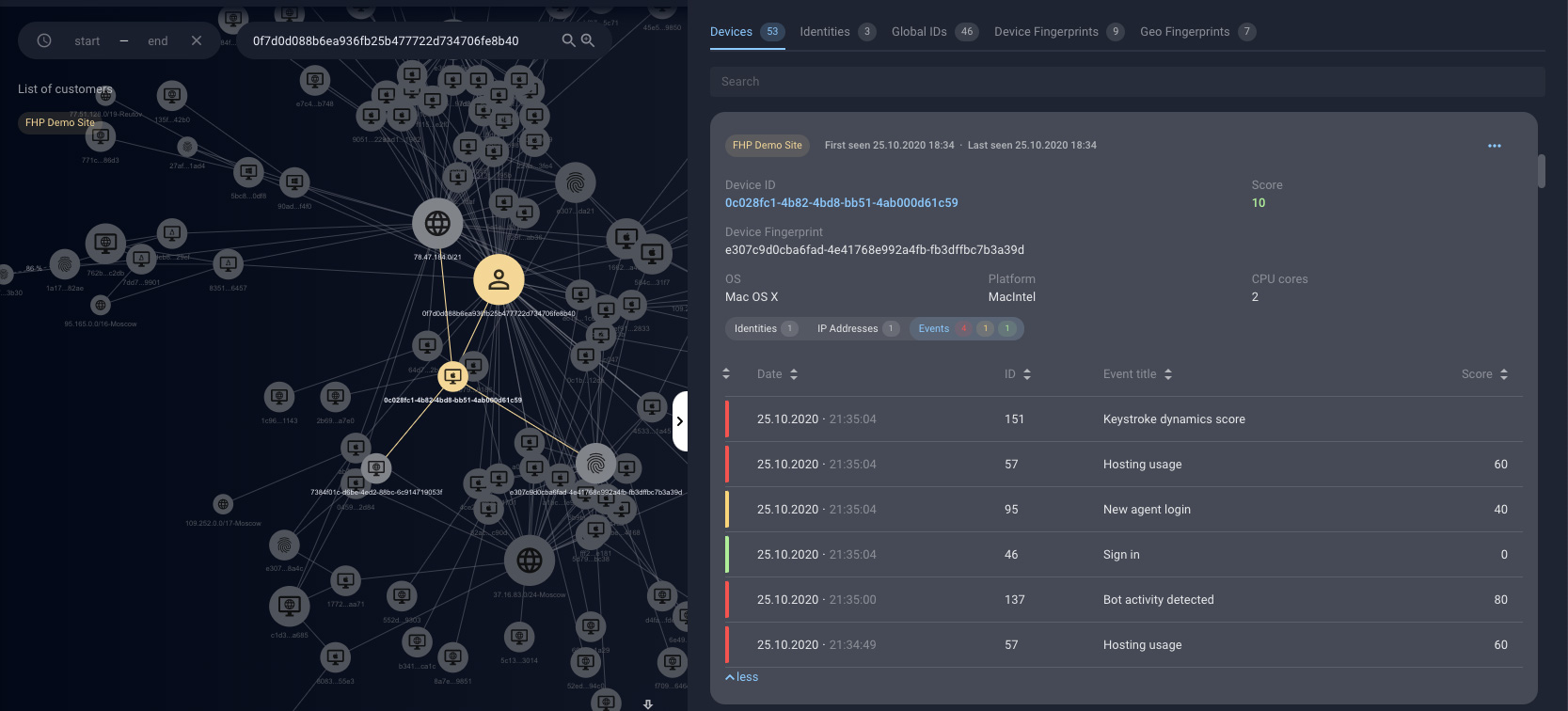

The FHP tracks visitors of the monitored sites by their device and session. Based on that information, it creates the user’s “identity”. It captures data available to the web browser context (platform specification, browser plugins, mouse and keyboard movements, tab active/inactive), but also network-related data (User-Agents, IPs, etc.).

This data is analyzed and used to generate alerts that identify bots and malicious events. Every alert is marked with a score from 0 to 100 (the higher score represents a higher risk). Event detection is not based on signatures – it’s achieved through machine learning algorithms that are trained on previously collected data and appropriate intelligence feeds.

Figure 2. Fraud Hunting Platform – mouse pattern

Figure 3. Detected sessions and event summary in the Fraud Hunting Platform

The FHP does not need users to be logged in the monitored site to “identify” them. Users’ identity is based on the user’s device fingerprint, i.e., the context within which they are accessing the site. The device fingerprint is derived from various data points: User Agent, operating system, time zone, fonts in use, browser plugins, language, MIME types supported, Canvas fingerprint, emulator usage, cookie parameters, media devices, DirectX and WebGL parameters.

Figure 4. Graph showing keystroke dynamics

As noted before, the user’s behavior is a signal that also helps determine the user’s identity. Behavior analysis is based on the user’s speed and navigation, mouse movement patterns, typing cadence, and interaction with form fields.

Figure 5. The session details show the triggered alerts. In this example, a suspicious visitor logged in with multiple accounts after changing his device and IP address. The FHP also detected that the login was performed by a password copied from clipboard

The FHP detects abnormal user events such as IP and location changes, use of VPN/TOR, proxy use, and User-Agent and OS changes while accessing the monitored site. The FHP also detects automatization technologies such as PhantomJS and Selenium, which mimic user behavior and web page interaction.

Figure 6. Detection of an RDP (Remote Desktop) session

The FHP can detect malicious injects and remote sessions. Attackers or malware can inject malicious JavaScript code into a website to change its structure or to enable Man-in-the-Browser attacks, with the ultimate purpose of stealing user information. In the FHP Script section, the service owner can configure which script will be treated as dangerous and which as a false positive (e.g., if they use third-party services that change their site’s structure).

Figure 7. Detection of a JavaScript inject

Some attacks involve the use of remote access tools like RDP, VNC, TeamViewer, etc. The FHP can detect them.

Figure 8. Detected script injections can be audited and classified as benign to prevent false positive detections

Figure 9. When using the mobile SDK, the FHP can detect rooted devices and insecure permissions and settings

Mobile SDK can also detect the use of remote access tools, trojans using Accessibility Service (which is currently employed by such trojans as EventBot, Ghimob, Gustoff), and overlays.

The Preventive Proxy

The FHP uses a component named Preventive Proxy to react to detected bot activity. The Preventive Proxy is a policy-based module that is used to detect traffic type and to define actions related to specific bot detection. It either works on all incoming traffic or on individual requests.

After analyzing the device data and user behavior, the FHP can detect whether a specific request to the application API is generated by a bot or is the result of legitimate user activity.

Based on the FHP’s verdict, the Preventive Proxy can, in real time:

- Pass legitimate request

- Mark suspicious request

- Block malicious bot request

Figure 10. The Bots section contains the detections related to the Preventive Proxy

Some of the scenarios where the Preventive Proxy comes useful as a blocking technology are:

- Unethical scraping and use of automation tools (e.g., Selenium) to mimic users

- Brute-force login attacks

- Credential stuffing

- Application-level DDoS

- Cookie theft

- Unauthorized API use

The Preventive Proxy can be tightly integrated with the load balancer serving the website. Two implementation scenarios are possible:

- In the first, the Preventive Proxy is used as an advisor that messages the load balancer on the bot events that should be blocked (Advisor mode). The events are transmitted in the HTTP Header and the balancer should be configured to act according to those events.

- The second scenario is a classic inline installation where the Preventive Proxy acts as a real proxy and blocks detected malicious traffic. For testing purposes, the Preventive Proxy can be set in monitoring mode (to propagate events and not block traffic).

Investigation

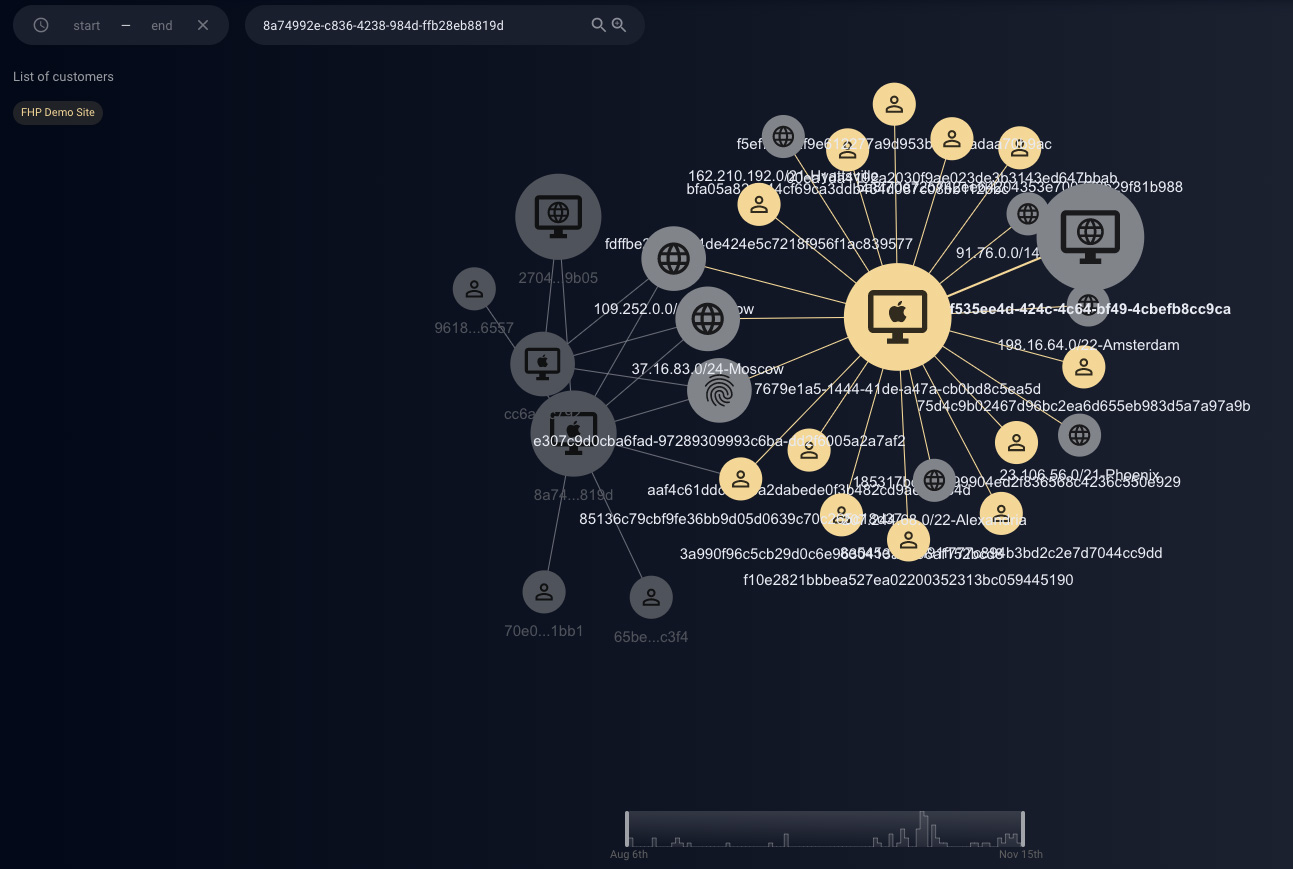

The analytical part is where the Group-IB Fraud Hunting Platform really shines. The Investigation section in the web interface provides useful visualization capabilities based on graph analysis. The graph view allows the investigator to dig deeper into the details of potential incidents and connect the dots between multiple threat actors that are attacking the monitored web site.

The Investigation section allows service owners to search and analyze connections between IP addresses, devices and user identities. They can build a graph based on the data that can be found in the Fraud section, such as IP address, subnet, Identity, Device identifier, or Global ID (we will discuss this identifier in the next section).

Figure 11. Investigation – a graph view shows interconnected devices and multiple identities accessing the monitored site from different locations

The Investigation section provides a good summary for detecting attack patterns that are less obvious and involve a lot of data and interdependencies. The Investigation view can be beneficial while investigating specific cases and for faster resolution of various techniques that attackers use. For example, in cases where attackers use stolen information to perform payment fraud, access private data or perform money laundering, they try to hide their traces by rotating their originating IP address or they spoof their access details. Investigation with the available graph can help fraud analysts to spot those patterns and reduce the time to detect the incident and perform remediation actions.

Figure 12. The Investigation section reveals a summary of events triggered by the user

Global ID

Global ID technology provides globally distributed user identification, so if the service owner monitors different sites, they can correlate identified users that access all their monitored resources.

Web browsers (Chrome, Mozilla Firefox) have recently stopped storing third-party cookies by default. Global ID technology works even if this browser policy is enabled and allows users to be recognized regardless of restrictions. Global ID is usually used in the investigation of incidents, and it helps to establish links between devices and events used across all service resources.

Global ID does not require the collection of users’ personal information and does not disclose anything about the user except their identification number and can be recorded on a different permission level (global, country, region and organization level). This enables Global IDs to be exchanged between FHP users that use the same level, so that they will be alerted when an attacker with a previously known Global ID starts probing their services.

Global ID identifiers exchanged across different protected resources can help investigations that analyze fraudulent activities on a larger scale (e.g., in cases when multiple financial institutions or branches are involved in money laundering or payment fraud).

Figure 13. Global ID connects the use of different resources by the same threat actor

Final thoughts and verdict

The Group-IB Fraud Hunting Platform is an innovative product that performs bot and fraud detection well. FHP integration on the client-side is very simple. Back-end integration may be more or less difficult, depending on the selected implementation type (cloud or on-premises). The on-premises installation and a tight integration with other systems can require more time and planning. During the tests, no slowdowns were noted on the demo websites that we used.

The FHP provides more information than just plain event logging, because it collects user signals that are relevant for detecting frauds activities. The innovative features extracted from the raw data trigger alerts that can help remove blind spots that you were not aware of.

It can also compete with SIEMs in some use cases, but it’s more specialized and gives better insight to fraudulent activities than just doing log correlation would. In other words, the FHP will help you detect fraud and malicious activity faster than your SIEM.

FHP’s bot detection capabilities and the blocking performed by the Preventive Proxy can provide a better mechanism for blocking bots than popular CAPTCHAs. The Preventive Proxy does not need any supervision for blocking successive bot requests when they are detected, while CAPTCHAs – when broken – enable attackers to access all the resources through session reuse.

We have tried scraping the demo website without success. The Preventive Proxy marked all responses to our scraper requests as “403 Forbidden”. The FHP also makes use of the Group-IB Threat Intelligence database so some targeted attacks to services can be spotted early in the kill chain.

We liked using the platform. No prior training is needed because it’s very intuitive, elegant and slick (it also comes in dark mode by default). A gentle learning curve means that you can onboard threat and fraud analysts to use the FHP in minutes, instructing them on just the essential concepts. The FHP will not overwhelm them with a lot of details but give them the ability to pivot their search based on their investigation interest. Events that need additional action are visible and emphasized with colors depending on the risk factor.

The part we liked best is the investigation capabilities. The Investigation is based on graph (network) analysis and can save analysts a lot of time while they are analyzing access patterns. It provides a good summary of events and other relevant details to the investigation (e.g., geolocation, identities, device information, etc.). The Global ID is a great add-on that helps bridge various access patterns between services and can help spot specific attacker groups patterns that are potentially targeting one’s service.

Based on the conducted tests and the investigation capabilities, we can recommend the Group-IB Fraud Hunting Platform to those who are searching for more insight about users of their web service(s) or mobile application(s), or to those who want to improve the fraud detection process in their company.