Google discovers websites exploiting iPhones, pushing spying implants en masse

Unidentified attackers have been compromising websites for nearly three years, equipping them with exploits that would hack visiting iPhones without any user interaction and deliver a stealthy implant capable of collecting much of the sensitive information found on users’ iOS-powered devices.

Indiscriminate compromise

“Earlier this year Google’s Threat Analysis Group (TAG) discovered a small collection of hacked websites. The hacked sites were being used in indiscriminate watering hole attacks against their visitors, using iPhone 0-day,” shared Ian Beer, a researcher with Google’s Project Zero.

“There was no target discrimination; simply visiting the hacked site was enough for the exploit server to attack your device, and if it was successful, install a monitoring implant. We estimate that these sites receive thousands of visitors per week.”

Subsequent research revealed the attackers’ use of five unique iPhone exploit chains, using 14 vulnerabilities covering almost every version from iOS 10 through to the latest version of iOS 12, meaning that the attackers made “a sustained effort to hack the users of iPhones in certain communities over a period of at least two years.”

Of the 14 vulnerabilities, seven affected Safari (i.e., WebKit, its browser engine), five the kernel and two allowed sandbox escapes.

“Initial analysis indicated that at least one of the privilege escalation chains was still 0-day and unpatched at the time of discovery (CVE-2019-7287 & CVE-2019-7286). We reported these issues to Apple with a 7-day deadline on 1 Feb 2019, which resulted in the out-of-band release of iOS 12.1.4 on 7 Feb 2019,” Beer noted.

“For many of the exploits it is unclear whether they were originally exploited as 0day or as 1day after a fix had already shipped. It is also unknown how the attackers obtained knowledge of the vulnerabilities in the first place,” Google Project Zero researcher Samuel Groß explained.

“Generally they could have discovered the vulnerabilities themselves or used public exploits released after a fix had shipped. Furthermore, at least for WebKit, it is often possible to extract details of a vulnerability from the public source code repository before the fix has been shipped to users.”

More details about the spying implant

According to the researchers, the implant is primarily focused on stealing files and uploading live location data, and beacons to and requests commands from a C&C server every 60 seconds.

It can access:

- Users’ photos, contacts, location data (GPS)

- The device’s Keychain, which contains credentials, certificates and access tokens (e.g., the Google OAuth token)

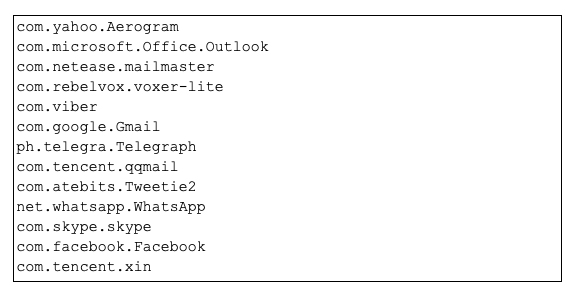

- Container directories containing all unencrypted messages sent and received via popular end-to-end encryption apps and mail apps (including Telegram, Gmail, QQMail, Whatsapp, WeChat, and Apple’s own iMessage app).

But, interestingly enough, the implant binary does not persist on the device.

“If the phone is rebooted then the implant will not run until the device is re-exploited when the user visits a compromised site again,” Beer noted.

“Given the breadth of information stolen, the attackers may nevertheless be able to maintain persistent access to various accounts and services by using the stolen authentication tokens from the keychain, even after they lose access to the device.”

Who’s behind this?

The researchers didn’t publicly identify the hacked sites (“watering holes”), which is information that could allow us to make an educated guess about the targets and the attackers.

It seems obvious, though, that the attackers have considerable resources at their disposal and, judging by the capabilities of the spying implant, are not financially motivated. In fact, it all points to a long-standing effort supported by a nation-state.

Rendition Infosec founder (and former NSA hacker) Jake Williams told Wired that these campaigns bear many of the hallmarks of a domestic surveillance operation. Still, the fact that the implant uploads the data without HTTPS encryption and to a server whose address is hardcoded in the binary is unusual for such an effort.

“Contrast that with multiple exploit chains and sandbox escapes and it sure sounds like a group with tons of money to buy exploits and little operational experience,” he noted.

The non-disclosure of watering hole sites’ and C&C server’s IP addresses combined with some of the language in Google’s blog posts has spurred online speculation.

Breadcrumbs in the story say ethnic minority groups in China. Now let’s wonder which ones could these be over the last few years? But C&C servers not disclosed.

— Lukasz Olejnik (@lukOlejnik) August 30, 2019

Current educated guess: Threat actor is a Middle Eastern oppressive government and specifically targets a group (dissidents/opp party/journos) via the unknown low traffic sites (indirectly discriminate). Money blown on exploit kits from talented folks with slapped on homegrown C2

— Aaron Grattafiori (@dyn___) August 30, 2019

All that aside, the most important realization resulting from this discovery is that iPhones are not as secure as generally and widely believed.

“The reality remains that security protections will never eliminate the risk of attack if you’re being targeted,” says Beer, and sometimes this might mean “simply being born in a certain geographic region or being part of a certain ethnic group.”

Users should be conscious of that fact and make risk decisions based on it, he concluded. “Let’s also keep in mind that this was a failure case for the attacker: for this one campaign that we’ve seen, there are almost certainly others that are yet to be seen.”

UPDATE (September 09, 2019, 12:50 a.m. PT):

Apple has disputed Google’s characterization of the attack.

“Google’s post, issued six months after iOS patches were released, creates the false impression of ‘mass exploitation’ to ‘monitor the private activities of entire populations in real time,’ stoking fear among all iPhone users that their devices had been compromised. This was never the case,” the company noted.

The attack was “narrowly focused” and “affected fewer than a dozen websites that focus on content related to the Uighur community.”

Apple also said that all evidence indicates that these website attacks were operational for roughly two months, not two years.

“We fixed the vulnerabilities in question in February — working extremely quickly to resolve the issue just 10 days after we learned about it. When Google approached us, we were already in the process of fixing the exploited bugs.”

Unlike Google, Apple had no qualms saying which was the targeted population.

Also, according to Volexity, there were Uyghur and East Turkistan related websites that targeted Android users, too.