Cybercriminals are increasingly using encryption to conceal and launch attacks

In this Help Net Security podcast, Deepen Desai, VP Security Research & Operations at Zscaler, talks about the latest Zscaler Cloud Security Insight Report, which focuses on SSL/TLS based threats.

Here’s a transcript of the podcast for your convenience.

Hello everyone. My name is Deepen Desai. I’m the Head of Security Research at Zscaler. In this Help Net Security podcast I will be talking about the latest Zscaler Cloud Security Insight Report that focuses on SSL/TLS based threats. This report was compiled from the data and intelligence that we gathered during the second half of 2018.

On a daily basis Zscaler Cloud Security Platform processes over 60 billion web transactions, and as of December 2018, 80 percent of these web transactions are over an SSL/TLS encrypted channel. This represents a full 10 percent increase, when you compare it to the same time-frame in 2017.

Google and Firefox also published similar stats and I’ll share that here. As per Google, the number of pages that were loaded over HTTPS, as compared to HTTP, was over 90 percent, as of December 2018. Now that’s a really high percentage of traffic that is internet-bound and is flowing over an encrypted channel.

One of the obvious questions is why is it so high? There are two primary reasons for the rapid growth in encrypted traffic over the past few years. The first and the most important one is the advent of free SSL certificate providers like Let’s Encrypt. Also, commercial CA’s have started offering free short-lived certificates. The second one is strict user data privacy requirements, which means lots and lots of website owners are moving their sites to HTTPS.

Data privacy is great and important, but what we are seeing in the past few years is that cyber criminals are actively taking advantage of this encrypted channel to conduct malicious activity across the board. In the second half of 2018, we saw 1.7 billion threats blocked over the encrypted channel on Zscaler Cloud. That’s a significant number, right?

What we’re seeing is a trend where the attackers are leveraging encrypted channels across the different stages of the infection cycle. It starts with the initial delivery vector, which is where common vectors include compromised sites, phishing pages, it could be malvertising attempts, where the user visits a perfectly legitimate site, and there is an ad that is getting loaded from a compromised ad server which starts the infection cycle.

There are also encrypted channels being leveraged to actually serve the exploit payload or the malware payload to the end user. Then finally, once the user’s machine is infected, we’re seeing the usage of SSL/TLS based connections for command and control activity, where the malware is actually attempting to call home.

Let’s talk about SSL or digital certificates. SSL certificates are used to establish an encrypted channel between the web server and the internet browser. These certificates include information about the owner’s identity as well as the digital signature of the entity that has verified the certificate. This is what all of you guys would know as CA, certificate authorities.

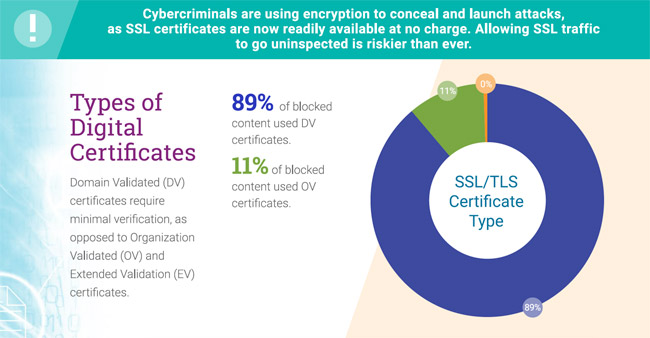

There are three types of certificates based on the verification methods that are used by a CA. The first one is domain validated cert, also known as DV cert. The CA is usually only valid if the person requesting the certificate has the ownership of the domain for which the certificate is being requested. This is a fairly easy to obtain certificate type. This typically happens by sending an email to the same domain which then gets asked by the original requester.

The second certificate type is organization validated, also known as OV certs. In addition to the DV checks, the certificate authority in this case will verify organization level details such as business name, physical address, before issuing an OV certificate. This essentially ensures additional trust for this certificate type. The name of the organization that the OV cert is being issued is also listed in the certificate details.

The third type is an extended validated cert, also known as EV certs. These are one of the more stringent form of validation performed by the certificate authorities. They include all their DV and OV checks, and also require verification of the requester’s identity by the CA.

The organization’s name and this certificate type will also appear in the address bar. If you visit a site, right next to the green padlock sign, you will also see the name of the organization to which the certificate was issued.

DV certificates by design are prone to abuse, as the attacker only needs to prove that he or she has the ownership of the domain. What we did at ThreatLabZ, we collected a bunch of certificates from a data set of security blocks that were captured over HTTPS, and we looked at the certificates from a few different angles. The first distribution that we studied was “hey, what are the different types of certificates that were involved in the security blocks?” No surprises here, we saw 89 percent of them were of the DV type, which are more prone to abuse. But then there were also eleven percent of the certificates which were of the OV type.

The obvious question over here is, how are OV certs being registered by malware authors? One thing I would clarify over here, as the OV certs typically are from legitimate web sites that have been compromised and were flagged for dropping malicious content during the period of compromise. The certificate is legitimate, the site is also legitimate. It’s just that the site was compromised, and it was serving bad stuff for a small duration during which that security block was accorded.

Next, we looked at the distribution of the certificates by the issuing certificate authorities and we saw that almost 50 percent of the certificates that were involved in security blocks over HTTPS were issued by Let’s Encrypt.

There were a lot of commercial CAs on this list as well, and there are two reasons for that. The first one is, many of this commercial CAs have started offering free short lived DV certificates, which are easy for an attacker to register as well. The second reason is, a lot of the legitimate web sites are also at times compromised. The cert is legitimate, site is also legit, but because the site is compromised, it has been configured to serve malicious content, which is why some of those commercial cert authorities are also appearing in this distribution.

Finally, we look at the distribution of the certificates by validity period, and that is how long is this certificate valid for. Nearly 74 percent of the certificates, that were either one year or under in terms of validity, were involved in security blocks, and a large percentage of the certificates were only valid for about 90 days. That’s another indicator.

We have three things over here. The first one is, the DV certificate types are heavily abused. They are generally issued by a free SSL cert provider, and then the validity of those certs is short lived, usually less than 90 days. This brings us to an important point.

Back in the days, users were trained to look for the green padlock sign in the web browser, as a symbol of privacy, trust and security. However, that is no longer a reliable strategy. Users need to be trained to look for additional indicators, like whether the organization’s name is appearing next to the green padlock sign. Remember the EV certificate that I mentioned? Then the URL itself before they choose to enter their credentials. The users need to be more aware of the page that they are visiting.

There is a recent Bank of America phishing example that we have included in the report to demonstrate this fact.

To conclude here, 80 percent of the internet bound traffic from the enterprise network is over an encrypted channel. This is a significant blind spot for modern enterprises that are not inspecting SSL/TLS traffic. Basic domain and IP-based filtering can help with a small percentage of these attacks, but the rate at which these cybercriminals cycle through this domains, it is always going to be a losing battle if you’re not inspecting the content.

Think of a payload that is being delivered through a site like Dropbox, or Google Cloud, or AWS, or an encrypted channel. This is where domain IP-based filtering will fail completely. My general recommendation is for every modern enterprise to have a balanced SSL inspection policy, as part of their overall security strategy. You don’t need to open up all TLS connections. You could exclude destinations going to healthcare, or finance, or government websites, but everything else you should inspect.

All the information that I covered in the podcast today is available in a report on our website at zscaler.com. You can always google Zscaler Cloud Security Insights Report and that should take you to the source. Thank you.