“I agree to these terms and conditions” is the biggest lie on the Internet

Two communications professors have proven what we all anecdotally knew to be true: the overwhelming majority of Internet users doesn’t read services’ terms of service (ToS) and privacy policies (PP), and those few they do, they do it far from thoroughly.

Despite this, all click on that button that says “I agree to these terms and conditions.”

The test

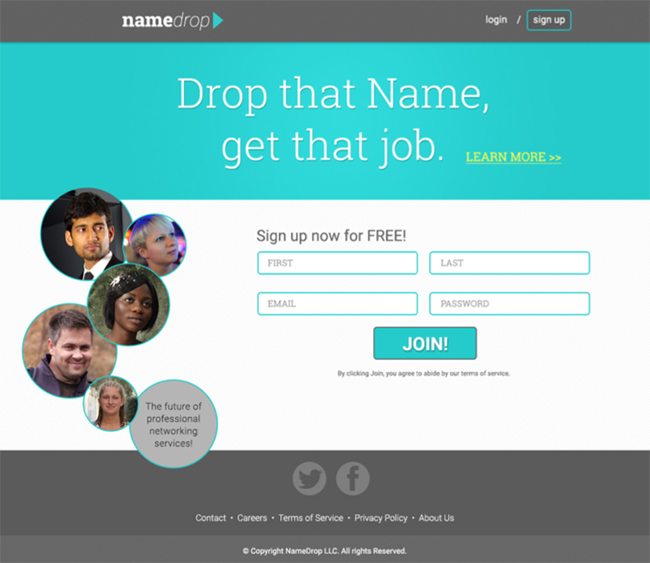

In order to see how many people read these documents before signing up for an online service, professors Jonathan Obar from York University and Anne Oeldorf-Hirsch from University of Connecticut set up a fictitious social networking site (SNS) called NameDrop:

They invited 543 students to sign up for it, and then asked them complete a survey that asked questions about their interaction with the privacy and ToS policy.

Both documents were modified versions of LinkedIn’s, and it would take users an estimated 29-32 minutes (PP) and 15-17 (ToS) minutes to read them. The ToS also held two so-called “gotcha” clauses: users would have to agree to allow NameDrop to share their data with third parties, including government agencies (e.g. the NSA), and to hand over their first-born child to NameDrop.

The results

Here are some of the results of the survey:

- 74% of the participants skipped PP altogether (they opted for ‘quick join’)

- The average reading time (of those who read the documents) was 73 seconds for the PP 51 seconds for the ToS.

- 96% of the participants spent less than 5 minutes on the PP and 97% spent less than 5 minutes on the ToS.

- Just 15% participants had concerns about the policies, and of them only 1.7% mentioned the clause about giving their child up, and 2% mentioned concerns about data sharing.

- More than 90% of the participants said that they use quick-join options often or sometimes.

- Often, participants found PPs and ToS to long and too wordy, and many just don’t read them because they are convinced that they wouldn’t understand them even if they read them.

More explanations that give insight into the participants’ thinking and decision making can be had in the paper.

The researchers noted that these dispiriting results are even more so when you take into consideration that the participants in the survey were communications students, who study privacy, surveillance and Big Data issues in class.

“If communication scholars-in-training cannot be bothered to read SNS policies, let alone demonstrate concern about the implications of ignoring notice opportunities, it seems likely that the general public would commonly ignore policies as well,” they pointed out.

It’s obvious that the current situation with PPs and ToS – the “notice and choice” policy – is a failure for users, and needs to be changed.